A RETURN TO THE FETID PIT

A new pack of scavengers, some still salt and sunburned from being pulled aboard the Apollyon and others with the hollow eyes of gaol habituates are escorted through the bustling central market of Sterntown, a neighborhood normally denied to them. The destination of the armed and armored scavenger gang is the Steward ramparts above the “Fetid Pit”. The revetments are sparsely manned, but bristle with flame sluices, spiked barricades, organ guns, arc lamps and volley darters all aimed down into the yawning air shaft that serves Sterntown as a sewer and chemical dump.

|

| Never Trust a Slime Mold |

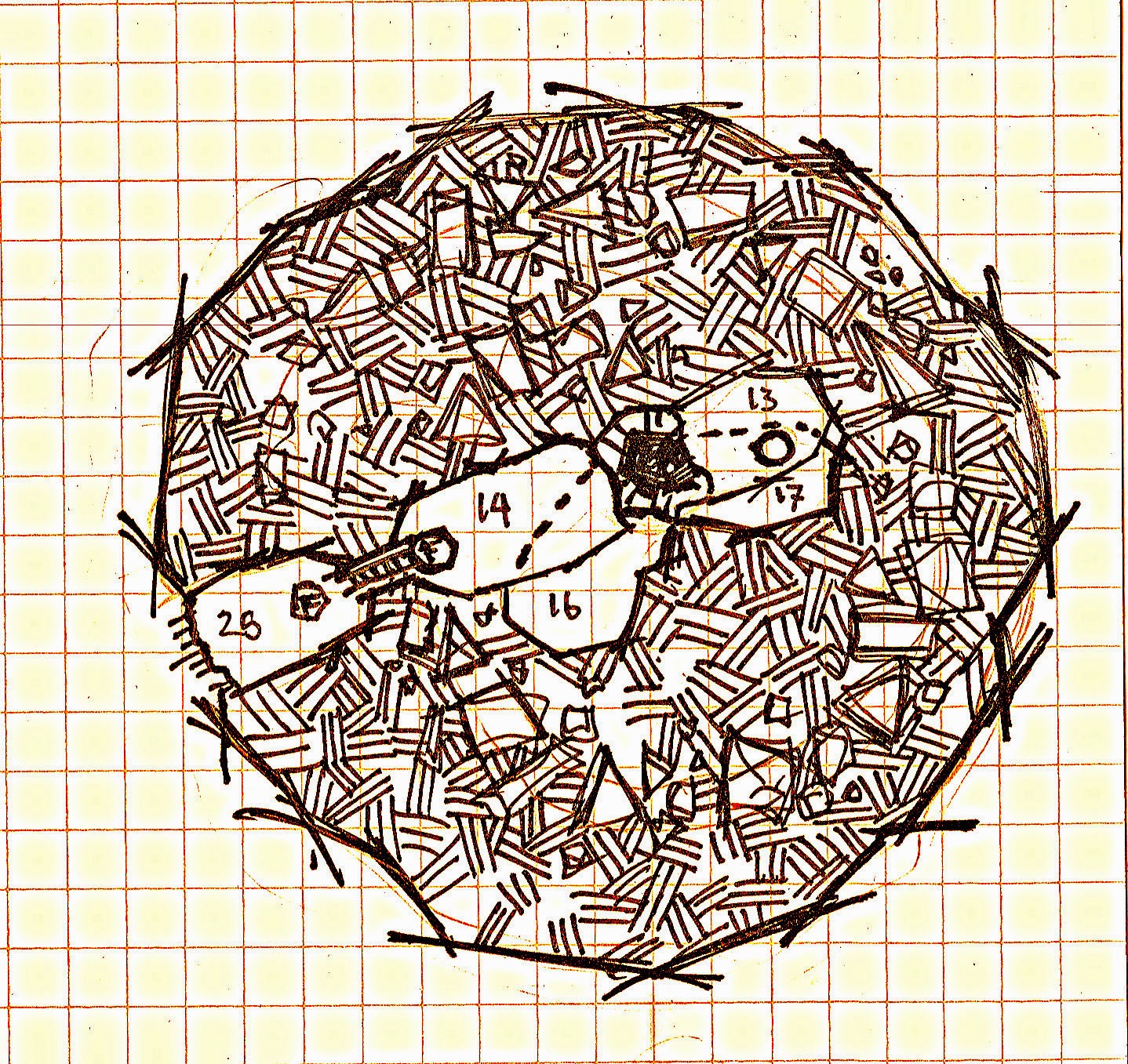

Told that they must descend by climbing a great chain dangling above the pit to recover valuables the scavengers look down. The ramparts are a tiny brightly lit and protected refuge in the wall of a vast shaft. Gray light trickles from far above, cut by the slow progress of titanic fans and dappled by a veritable jungle of fungus, molds, lichens and plants reaching for the light. Below the first hundred feet have been cleared to the oddly terrace hull metal, likely by the application of chemical and other industrial wastes, but beyond the vertical jungle begins again: pale spiny bromeliads the size of trees, dense tangles of black vines spouting tiny leaves, and a lurid variety of bright fungus. The grey light fliters down only 200’ feet revealing some sort of installation near the descent chain, but beyond is only blackness and flashes of bioluminescence.

The scarred Steward guards are friendly enough, offering to lower a basket to raise any booty when the party launches flares, and providing four blue roman candles for the purpose. The scavengers are told they will be honored with a full 50% share of anything they recover from the depths and to seek machine tools, industrial stocks and edibles in addition gold, silver and other obvious treasures. The latest draft of the unwanted includes

“Juan” – A doughty engineer with a penchant for pyromania.

“Mister Groob” – Another engineer, perhaps there’s something about working with machines that makes men inclined towards criminality and violence.

“Mister Groob” – Another engineer, perhaps there’s something about working with machines that makes men inclined towards criminality and violence.

“Briney” - An adept of the mysterious leviathan, his salt encrusted hair and robes reek of the sea.

“Hisala” – Some sort of vile reptilian manthing, perhaps an unsuitable byblow of an uptown family, perhaps a voyager from a distant sphere, alchemist.

“Son of Von Lumpwig” – A dull witted looking, half drowned fellow of unknown craft – a dab hand with the crossbow. “Ulwin” - An inquisitor and witch smeller of the Temple of the Eternal Queen. Von Lumpwig makes him very uneasy.

“Son of Von Lumpwig” – A dull witted looking, half drowned fellow of unknown craft – a dab hand with the crossbow. “Ulwin” - An inquisitor and witch smeller of the Temple of the Eternal Queen. Von Lumpwig makes him very uneasy.

“Clearwater” – A gladiator pulled from the sea, wearing decorative armor and adept with the net and trident.

The scavengers begin their descent and discover the chain is remarkably stable and fairly easy to climb. Descending past the cleared area the walls of the pit teem with life as insects swarm over the odd plant life feeding a host of lizards, crabs and strange naked rodents. The climbers after passing into the foliage the climbers decide to avoid a bed of mollusks, clinging from the wall and tasting the air with long feathery feelers. Not much can be seen, as the climbers only light is a bulb of crushed glow kelp, shedding a sickly green light that barely allows the adventurers light to find the monumental chain links beneath them.

Soon the climber stop, finding themselves at some sort of deck, where the chain continues down into darkness through a hole cut in the wire and corrugated iron flooring. Once the scavengers light a pair of torches the deck area and the strange building it serves becomes clearer. A ramshackle greenhouse, built from recycled panels of scavenged glass and a rusted frame juts out into the pit, with a small door leading inside, while a pair 10’ of ancient doors lead into the wall below a decaying sign that reads “Sterntown Agricultural Station #4” in letters blistered with time. Peering through the mismatched glass of the house reveals only a tangled jungle of dead vines splotched with pinkish lichen, while the doors prove to be unlatched and easy to swing open.

Within the station the scavengers barely have time to see that they are on some sort of warehouse floor, surrounded by decaying crates and drums, before a trio of pinkish beasts flapping on ragged rose colored wings descends on them. Mr. Groob is struck, and one of the horrors latches onto his face, its worm body opening into a single maw of thorn like teeth to gnaw at his scalp and drain Groobs blood. Thrown into confusion the party tries to fight back and while the combat is a swirl of daggers and razor teeth the attached flying worm is cut loose and the other two batted to the floor and slaughtered. Groob examines his tormentor to discover that the life form seems lack any organs, and is a solid pinkish sponge throughout, while others look around the warehouse.

Behind a row of crates, filled only with the moldered remains of agricultural goods the party discovers three huge sacks of chemical fertilizer, a potentially valuable commodity, as well a door leading deeper into the hull and a archway, partially clogged with some sort of irrigation device with a room beyond crammed with elevated bed filled with rich soil. In their search for treasures, the scavengers are more interested in the office that looms above the warehouse floor. Climbing the stairs Ulwin and Juan discover a locked office filled with simple metal furniture, stacks of paper, a pair of metal steamer trunks and a huge pulsing mass of pink fungus, covered in innumerable clear cysts, each containing neonate flying worms. Resolving to claim the chests, and incinerate the birthing mass, the scavengers set a clever plan into motion. Ulwin, Juan and Clearwater dash into the room and snatch the trunks. The mass shakes on convulses, birth a pair of hungry flying worms which the trio fend off. Groob stand in the doorway with a Molotov cocktail and a torch as his companions flee down the stairs, trunks banging behind them. More winged terrors pop from the shaking mass as Groob hurls the bomb and it spreads a curtain of flame over two of the emerging creatures as well as his target. Hisila using his magical command over fire turns the smouldering oil fire into an inferno reducing the mass of fungus to ashes and then damps the rest of the room into sullen embers. Exploring a desk in the office’s center Ulwin finds a valuable silver pen and ink set.

The noise of battle has not gone unremarked, and as the party descends from the plundered office in triumph several more of the worm creatures flap into their circle of torchlight. Choosing to retreat rather than fight, the adventurers dash out the double doors back onto the ledge, smash open the feeble locks on the trunks they recovered and debate where to go next. One trunk contains old ledgers, but the other holds a set of books on lightless horticulture, specifically the production of edible fungus, certainly worth something to the mushroom farmers of Sterntown.

Within the station the scavengers barely have time to see that they are on some sort of warehouse floor, surrounded by decaying crates and drums, before a trio of pinkish beasts flapping on ragged rose colored wings descends on them. Mr. Groob is struck, and one of the horrors latches onto his face, its worm body opening into a single maw of thorn like teeth to gnaw at his scalp and drain Groobs blood. Thrown into confusion the party tries to fight back and while the combat is a swirl of daggers and razor teeth the attached flying worm is cut loose and the other two batted to the floor and slaughtered. Groob examines his tormentor to discover that the life form seems lack any organs, and is a solid pinkish sponge throughout, while others look around the warehouse.

Behind a row of crates, filled only with the moldered remains of agricultural goods the party discovers three huge sacks of chemical fertilizer, a potentially valuable commodity, as well a door leading deeper into the hull and a archway, partially clogged with some sort of irrigation device with a room beyond crammed with elevated bed filled with rich soil. In their search for treasures, the scavengers are more interested in the office that looms above the warehouse floor. Climbing the stairs Ulwin and Juan discover a locked office filled with simple metal furniture, stacks of paper, a pair of metal steamer trunks and a huge pulsing mass of pink fungus, covered in innumerable clear cysts, each containing neonate flying worms. Resolving to claim the chests, and incinerate the birthing mass, the scavengers set a clever plan into motion. Ulwin, Juan and Clearwater dash into the room and snatch the trunks. The mass shakes on convulses, birth a pair of hungry flying worms which the trio fend off. Groob stand in the doorway with a Molotov cocktail and a torch as his companions flee down the stairs, trunks banging behind them. More winged terrors pop from the shaking mass as Groob hurls the bomb and it spreads a curtain of flame over two of the emerging creatures as well as his target. Hisila using his magical command over fire turns the smouldering oil fire into an inferno reducing the mass of fungus to ashes and then damps the rest of the room into sullen embers. Exploring a desk in the office’s center Ulwin finds a valuable silver pen and ink set.

The noise of battle has not gone unremarked, and as the party descends from the plundered office in triumph several more of the worm creatures flap into their circle of torchlight. Choosing to retreat rather than fight, the adventurers dash out the double doors back onto the ledge, smash open the feeble locks on the trunks they recovered and debate where to go next. One trunk contains old ledgers, but the other holds a set of books on lightless horticulture, specifically the production of edible fungus, certainly worth something to the mushroom farmers of Sterntown.

Emboldened, the tangled vines of the greenhouse no longer seem quite as threatening to the fortune hunters, but when Groob opens the door and enters he fails to spot a flock of the horrible pink winged worns, hanging like rotten fruit amongst the dead vines. Several of the vile creatures wing towards to wounded engineer, but Groob has the presence of mind to dash backwards and firmly close the door. Somehow sensing life and food beyond the greenhouse glass, the entire flock, nearly twenty strong begins to flutter and scratch against the glass. The party stands shocked, as the likely fungal horrors rattle against the flimsy seeming panes, but soon grow confident that the beasts cannot escape. While Groob distracts the things, striding back and forth before the glass manfully, the rest of the scavengers scurry back into the double doors, hopeful that the winged death remains transfixed on the Engineer. The gamble pays off and soon the party, except for Groob, stands at the rear of the warehouse and tries the crooked door there.

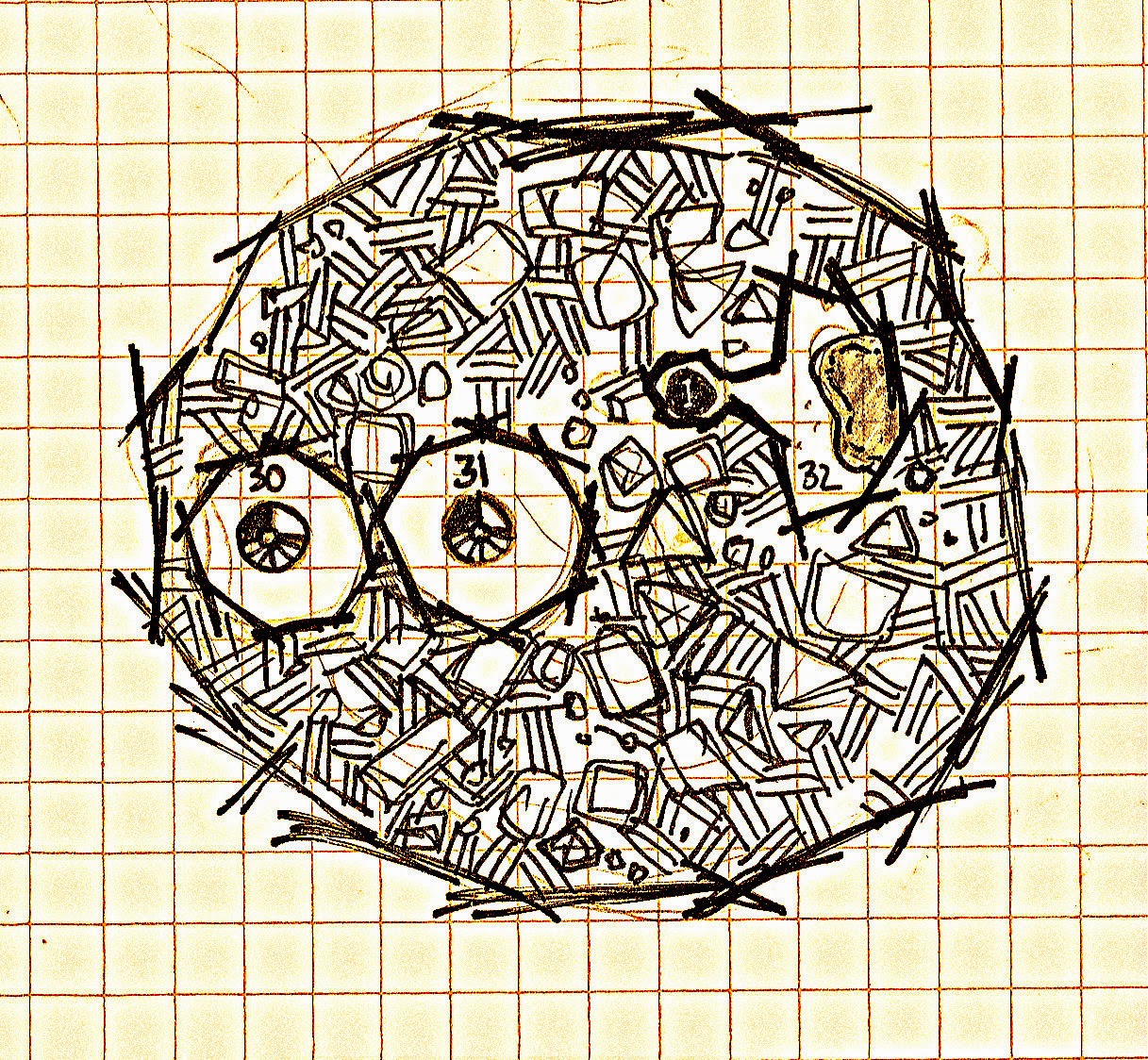

Beyond the door are the remains of a rough barracks with four sets of bunks, each with sheeted forms laid to rest on them. When the forms don’t move, the adventurers scan the room, noticing a kitchen with a simple iron stove and a mess of rusted pans in the rear, a curtained area, likely containing sanitary facilities, and more ominously that the sheets covering the dead are splotched with rose tinted lichen. With no respect for the dead, Son of Von Lumpwig fires a crossbow bolt at one of the corpses, but it missing banging off the bunk’s metal frame. The noise is enough to wake the quartet of fungal zombies, and they stride forward, arms outstretched, still tangled in their burial shrouds. Von Lumpwig calmly reloads and shoots a quarrel into one of the advancing creature’s skulls, while Ulwin attempts to drive them off with divine grace, realizing as he does so that the walking corpses are not undead, but rather the hosts for some sort of vile reanimating infestation. Retreating through the door, the other walking dead are quickly slaughtered with poleax and trident blows. Triumphant again the adventurers quickly ransack the barracks, finding a huge silver trophy cup amongst the kitchen’s debris. It is engraved “Grande Prix, Largest Mushroom, 15th annual Sterntown Fungiculturalist’s Ball” and worth several hundred coins.

Retreating with their find the adventurers collect Groob, still strutting bravely before the trapped flock of angry worm things, and decide to signal the Steward’s above. A blue flare screams off into the darkness, with no reply from above. The adventurers are about to fire another when a huge bioluminescent form begins to rise from below. As it approaches the beast appears to be some sort of enormous gas filled piscine nightmare, much like an angler fish and eight feet in diameter. Deciding that the fish means them harm, an oil flask is hurled directly into it’s face as it approaches. At twenty feet away Groob shoots his pistol into the creature, but neither the reek of oil nor the impact of the ball seem to distress the creature. The other adventurers begin to fire the remaining signal flares at the fish’s balloon like sides, and two flares spark off unsuccessfully before the last catches the creature in the side, igniting the oil and quickly burning to the gas beneath the creature’s skin. The fish explodes in a blast of heat and rolling green flame, that knocks several of the adventurers to their knees, but provides a signal that even the most jaded of Steward’s cannot ignore, and soon a basket is lowered for the scavengers and their loot.

Retreating with their find the adventurers collect Groob, still strutting bravely before the trapped flock of angry worm things, and decide to signal the Steward’s above. A blue flare screams off into the darkness, with no reply from above. The adventurers are about to fire another when a huge bioluminescent form begins to rise from below. As it approaches the beast appears to be some sort of enormous gas filled piscine nightmare, much like an angler fish and eight feet in diameter. Deciding that the fish means them harm, an oil flask is hurled directly into it’s face as it approaches. At twenty feet away Groob shoots his pistol into the creature, but neither the reek of oil nor the impact of the ball seem to distress the creature. The other adventurers begin to fire the remaining signal flares at the fish’s balloon like sides, and two flares spark off unsuccessfully before the last catches the creature in the side, igniting the oil and quickly burning to the gas beneath the creature’s skin. The fish explodes in a blast of heat and rolling green flame, that knocks several of the adventurers to their knees, but provides a signal that even the most jaded of Steward’s cannot ignore, and soon a basket is lowered for the scavengers and their loot.