THE MASTER GAME

![]()

I have been thinking about high level games, how bizarre and impossible they seem now, when I mostly want to play and run games where tragically human, limited and fragile characters face off against the mythic underworld or cunning and merciless over-world factions dependent less on the dice then on player wit.

Yet, high level play was a staple of my pre-teen D&D adventures, characters of 20

th and 30

thlevel fighting hordes of lichs riding red dragons, polymorph spells on every magic user's tongue, and a plus five holy avenger in every fighter’s fist.

TSR recognized this style of play, and produced product for it, specifically the ”black box” Master Set (levels 25 -35) of D&D in 1985, followed by the Immortal set in 1986 for characters that have ascended to demigod status.

These are still strange rulesets, especially the Immortal Set, which while a good idea, appears to have completely changed the rules of D&D and is complex and strange. The Master Set though struggles with the hard questions of terribly powerful characters and appears to fall back on the answer of limiting casting ability, but which I otherwise remember as having sound advice. This anti-magic bent isn't a surprise, as I suppose the another method is to simply allow everyone/everything in the game to cast as a 35

th level magic-user, making a game similar to the board game Nuclear War, where fights end as spheres of annihilation and disintegration rays leap from either side, pass in the air, and end the campaign.

I doubt there’s much need for high level play advice in the OSR circles I frequent (though Simon at

… and the sky full of dust has just finished

Session 127 of his Against the Giant’sCampaign and it looks like things are getting Spelljammer). Still the Master set poses interesting questions, and the Immortal Set is tempting - I find myself drawn to see how these old TSR sets tried to handle the difficulties of high level games.

TWILIGHT CALLING

Twilight Calling, is a “Master Game Adventure”, written by Tom Moldvay in 1986, as a way to bring the overpowered adventure party (levels 30 -35) into the Immortals game, and it actually has some interesting elements for high level play as well as a an eminently steal-able set of basic premises for any level of play. I’m surprised by this, Twilight is a post Dragonlance production and the production quality looks like those modules, but it has few of the marks of TSR’s mid-late 80’s shift from swords and sorcery freebooting sandbox play to directed, morally pedantic high fantasy. Perhaps this is because it’s from 1986, the same year as B10 Night’s Dark Terror, and Twilight is written by Moldvay with design credits to Paul Jaquays and Bruce Heard. This isn’t to say Twilight Calling is amazing, but it does manage to ramp up the strange to a level appropriate to near immortal characters messing with the machinery of the divine, and it’s problems (linearity, some anti-magic tricks, over reliance on combat and a certain frustrating disjointed episodic quality) are at least partially the result of an extremely strange setting and the difficulty of providing a challenge to 35thlevel characters.

It might be interesting to note that Twilight Calling's chromatic worlds are based on Alchemical Allegory of planets, colors, humors and metals. This product was published in 1986, a year after Mazes and Monsters was released and in the midst of the 'Satanic Panic' and controversy surrounding Dungeons and Dragons as an enticement to witchcraft. As silly as this seems now, this module is the only D&D product I've ever seen that actively and explicitly references real world superstitions about magic. It doesn't do it especially well, and Alchemy seems to have been more about spiritual transcendence within a Christian world view then diabolism, but consider the ramifications here and take a moment to cheer Moldvay's enormous hobbyist chutzpah.

AN IMMORTAL PLOT

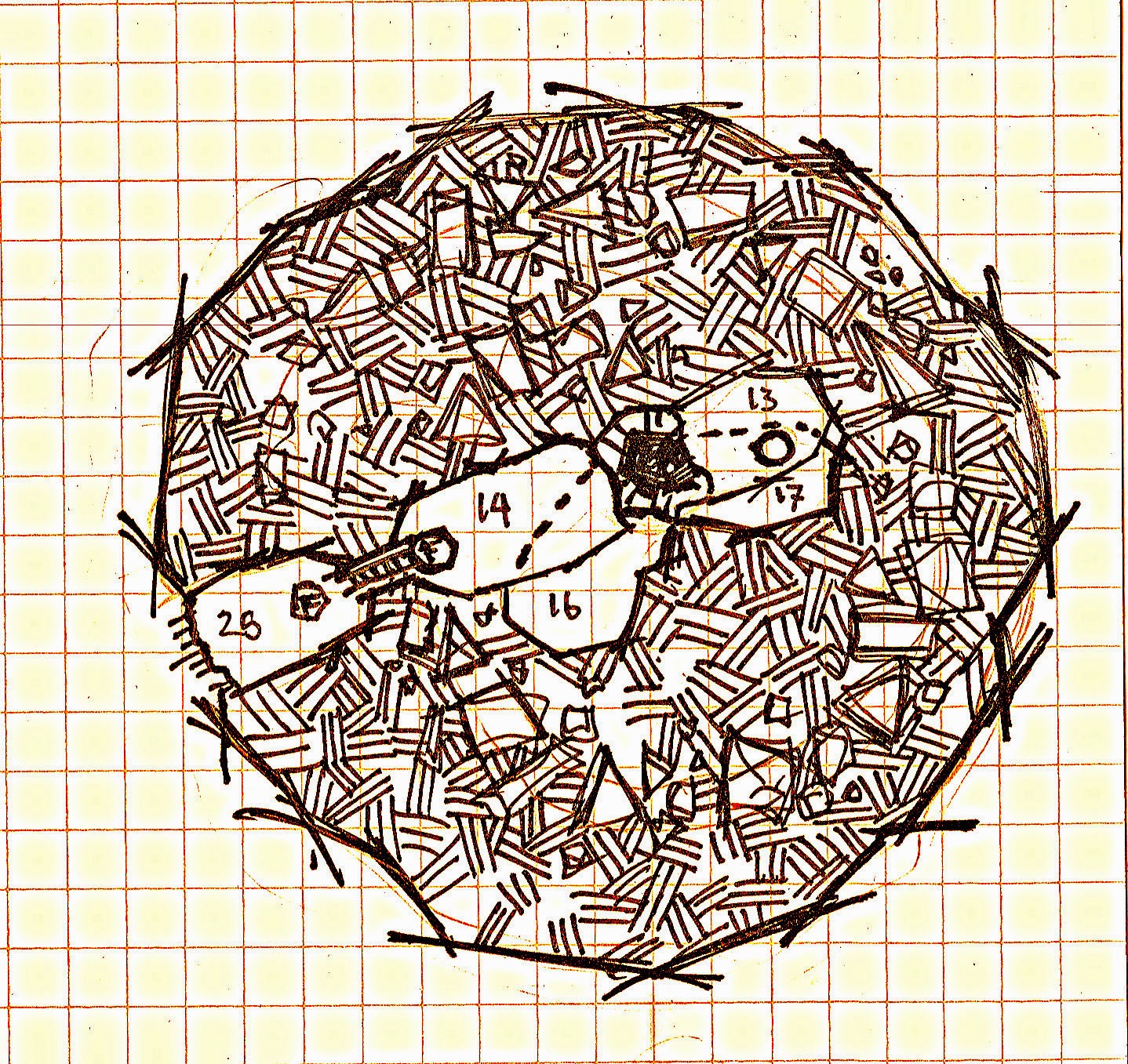

![]() |

| Shouldn't a PC be Weirder at 35th Level? |

One of the lesser deities of chaos has decided to rise in the hierarchies of the night by tricking a band of powerful mortals into releasing an ancient evil locked away in a pocket universe, behind several other pocket universes. He selects the party as the instrument of his plan, because only ‘good’ mortals can break the various barriers that prevent the escape of an ancient race of evil dinosaur sorcerers from their endlessly falling stone citadel amidst the void of an empty pocket universe (alright, it actually floats there, and would be better if it was made from magic and the bones of the dinosaur wizards' dead). To do so the evil godling (I’m not using the horrible D&D names of anything from the module in this review – the dino-sorcerers are called ‘Carnifex’ for example – ugh) send a mad prophet tossing about gems to the PCs' stronghold. The lunatic utters a prophecy about a gateway and the return of the dinosaur wizards, telling the characters just enough to research the gateway’s location, implying that it’s full of treasure and warning the danger of the trapped evil, while hinting it is about to return. The messenger then crumbles to dust and if speak with dead is used on him the evil god replies, trying to trick the party into going to the gate and entering, while imploring them to travel into the prison dimension and destroy the evil there.

The party can then do a bunch of library research at an ancient library and gather an extremely large number of useful clues and rumors. Entering the chromatic realms that guard the prison universe is itself a bit of an adventure, a few days of overland travel to an ancient stone circle and then discovering references to the seven color themed realms ruling symbols (which must be recovered from their masters before entering the prison universe). Each of the realms is fairly interesting, and claim to be drawn from Medieval, likely alchemical, allegory. That’s a pretty great idea for a setting. It also is basically the plot of Jodorowsky’s Holy Mountain, but who am I to complain if TSR’s mid 80’s writers went beyond Tolkien for once looking for inspiration. The realms can be entered in any order and include:

The Rainbow Realm (Mercury - Quicksilver) is pretty much full of bad jokes and decent riddles, but it has some very strange monsters, stained glass knights and a lake of living poisonous quicksilver guarding an artifact wand. It’s generally a realm of mists and air, though not especially well described. None of the realms are really well described, a fact which should be rectified to push the otherworldly aspect of this adventure to a higher level, even if the module itself contains sufficient inspiration.

The Green Realm (Venus - Copper) is a place where good but aggressive elves linger in a wild forest and the realm’s corrupted elf queen lurks at the center of a formal garden. She’s very mythical seeming, guarded by swan Valkyries and attacking by charming the characters, but she must be fought. Once defeated the forest overtakes the garden, breaking insane queen's attempt at forcing nature into stasis for great allegorical pay off.

The Red Realm (Mars - Iron) is a world of war, with a roughly described Martian plain inhabited by monstrous representations of militarism, and a lunatic master whose blood turns into myrmidons. This is good stuff, if a bit clichéd (well all these realms are perhaps, but we can call it mythic instead), and what’s best about the Red Realm is that it doesn't emphasize fighting. The horrible monsters can be fought (and one or two guardians must) but the really dangerous ones - an enormous rushing war machine that is something like an entire weapon spouting army of soldiers fused together, and the realm’s mad charioteer master are best if avoided or allowed to attack until he gets bored and leave, having transfixed a character with the realm's magic symbol.

The Black Realm (Saturn - Lead) is a vile swamp, with some interesting encounters and a brooding master who sits on his own coffin in an obsidian pyramid. The realm’s inhabitants all evoke age and decay quite nicely, but sadly everything here attacks: blind ancient god-serpent, hag priestess, a huge basilisk and the strange philosophical master himself.

The Blue Realm (Jupiter –Tin) has been pulled straight from the Golden Bough, and can be mastered without combat, which is not a bad thing. It’s a plain of mannered fields and very lawful, with corn spirits that demand sacrifice and archons that will gift the players with flaming angelic swords if they behave.

The White Realm (Moon – Silver) A sea devoted of strange magic and seafoam horses, with an island at its center. This is another area where combat is constant and the realm’s strange inhabitants (giant mermen and white dragons), but its master is pretty cool, offering an archery contest or bargaining for a party member in exchange for her symbol. There’s also a small chance a party member will end up with a silver limb which is a nice touch.

The Yellow Realm (Sun- Gold) The first encounter is with a wounded gold dragon that is threatening, prideful and annoying, but won’t attack if ignored or helped. After that there’s a trapped cave (really the first trap so far), a curious phoenix and a powerful immortal sculptor who wants to spend years sculpting one of the characters.

Once the symbols have been collected the party can travel to the prison dimension where they get to explore a castle full of evil dinosaurs. This is the weakest part of the adventure, with a set of lame cooking themed traps (the dinowizards are cannibals and obsessed with cooking) and a room of undead (presumably undead dinowizards). There’s a final battle where the party must fight their own doubles which is nice enough, but really the castle itself feels like an aftermath.

Bad Design

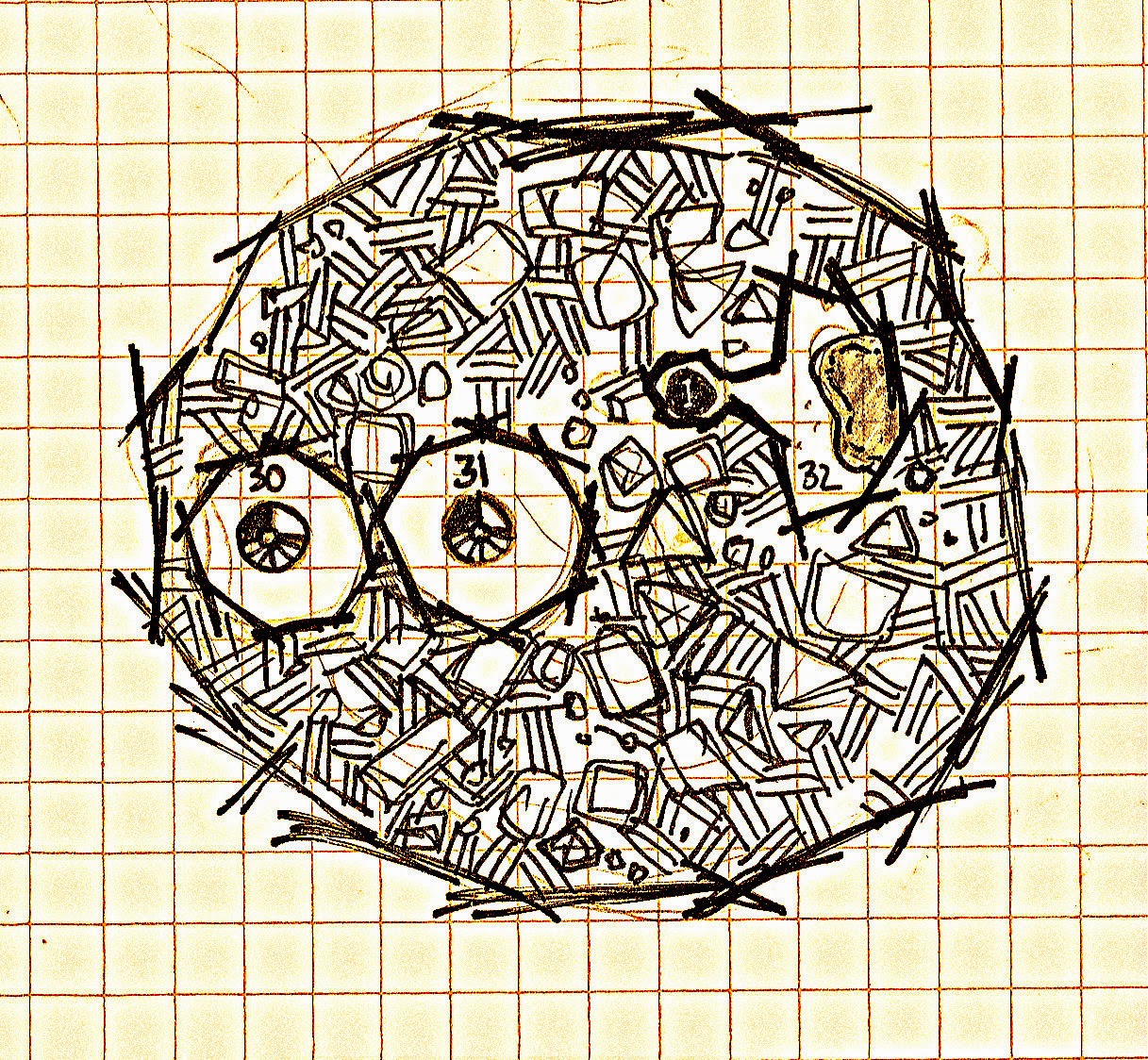

![]() |

| This is What Twilight Calling Should Aim For |

When Twilight Calling decides a fight is in order, a fight will happen. To some extent this is reasonable, when trying to steal the heart/treasure from a magically animate quicksilver lake for example, and ultimately that sort of fight can be avoided by not trying to take the treasure. Yet Twilight goes too far to encourage combat, and when it does so it often does it after pointless parleys. This isn’t to say there aren’t good examples of almost certain fights in Twilight, the mad sculptor who will attack if the party refuses to leave one of its members behind as a subject for his art is one, as this encounter contains a choice, it’s a bad one, but it’s there.

The creatures of the Green and Black realms however just have to fight, no matter what. This is made doubly annoying because they are cool mythical enemies (especially in the Black Realm) and would be interesting. That the denizens of these realms are interesting is a double shame, because Twilight Calling almost asks for faction conflict between the realms: Red vs. Blue, Green vs. Yellow and White vs. Black, perhaps – or all out for themselves, offering their symbols in exchange for the destruction or torment of their immortal foes.

The failure to capitalize on the iconic conflicts between the chromatic/alchemical/planetary realms in Twilight is compounded by their physical separation from each other and by bad maps. Well not bad maps exactly, the realm maps are simplistic and often pointless. It’s a shame really, because a single chromatic pocket universe could have offered a really fine sandboxinstead of a couple of light sandboxes and some real railroads, complete with quantum ogres. Some of the realms, the green and red, appear to be sandboxes to a degree and their are random encounters, but they are always very small sandboxes and the random encounters are all of the 2 in 6 chance of encountering a giant dragon. At least the decision about what order the realms can be addressed in is open and many of the individual encounters are quite interesting.

The castle of evil in the prison void is also under realized and it’s cooking puns really detract from the strange mythic feel of the rest of Twilight. Now I like a bit of humor hereand there, but a pit of poisonous barbeque sauce followed by a hall of red hot grills is Castle Greyhawk level gonzo stupid (as opposed to gonzo smart), and all the more because it’s the climax of an adventure that has a very different dream-like mythic feel. The dinosaur castle just needs to be removed or replaced. In general Twilight’s problems could be solved by allowing it to become the dreamscape sandbox that it seems to make gestures towards, and to really embrace the possibility that this is an adventure where the party will be immortal or retired at its end.

GOOD DECISIONS

The overall hook of Twilight is not sound, evil gods trying to trick powerful heroes into releasing ancient evils is a pretty compelling and very mythical classic. The way the hook is set up with a large (30 entry) table of clues from strange books in an ancient library (and the table notes each book as well, which is a nice touch) and a portal to some pocket universes is also pretty good. It doesn’t force the party into the chromatic realms, but what party will pass up a dude who turns to dust after a prophetic warning and the chance at godhood.

The pocket universes, and their chromatic themes are also really evocative. The module could have gone further in this direction and some of the realms (Green and Yellow) are a bit devoid of real crazed alchemical mythic flavor, but overall this is a great idea that really gives the module the feel of treading into the realms of the gods and machinery of the universe. Some of the results of the players' actions, specifically breaking the Green world’s stasis and destroying it’s beautiful garden in a sudden flurry of accelerated seasons, are excellent as well, giving a sense of dramatic change and the high stakes of immortal shenanigans.

The inhabitants of the various chromatic realms are also good fun, there is a reliance on too many giant dragons for basic enemies, but the unique monsters are interesting and appropriately strange. More importantly the enemies situational powers and abilities offer nice in game puzzles, including many enemies that need not, and likely shouldn’t, be confronted in combat - especially the red world’s fused legion monster that can be dodged, and offers no reason to fight it. It’s also good that it (and other non-combat designed encounters) can be fought, and likely defeated at the cost of burning large amounts of character resources, which the module carefully limits with some dull (but setting appropriate enough) prohibitions on spell and HP recovery. Monsters you can’t fight are boring, but monsters that you shouldn’t fight and needn’t fight are a good addition, especially in a high level game.

A BETTER TWILIGHT

This isn’t a bad module, it’s just a bit sketchy in places and doesn’t really want to embrace what it is – the twilight of a super powerful party's adventuring days. I like the choice of retire or ascend to the godhead for extraordinary heroes, and at level 35 there can’t be too many terrestrial foes left in the game world.

![]() |

| Properly Mythical and Esoteric |

I’d bend the hook a little to have the trapped dino-sorcerers be an alternate pantheon of evil gods (not the space tentacle variety, just some old gods trapped too long in a void and gone cruel, cannibal and strange). The evil gods' influence has been leaking into the guardians of chromatic realms and corrupting their perfect masters, until sometime soon they will themselves release the evil pantheon unto the world. The prison dimension could then become an optional part of the adventure, and the fundamental question for the party would be A) collect all the chromatic realm’s tokens and return them to the terrestrial world to trap the mad masters and mad pantheon in the chromatic realms and prison universe, retiring knowing they have saved the game world, or B) let out the mad gods, and seize the artifacts they leave behind, damning the game world, but promoting themselves to divinity and possibly allowing them to battle those they’ve released – and the current pantheon they’ve pissed off – because a three way divine war starts like a way to start an immortals campaign.

With the premise elevated to a game breaking/transforming level, I’d also join the chromatic realms into a single wheel like pocket universe, divided into pie slices with the portal to the prison dimension at its center. Each of the individual chromatic realms is pushing its borders against its others, the sanguinary red bleeding into the hopeless of the black swamp and honor of the yellow domain for example. Each of the more or less corrupted despots of the realms and the other immortal powers within the chromatic domains would desire to conquer or destroy their enemies. Suddenly there’s a seven faction allegorical conflict that does the subject material (alchemical mysticism) justice and allows the players to decide what sort of divine presences there characters might become by which allies they choose, which masters they replace and what artifacts they seize. The realms are largely allegorical: rainbow = magic, red = war, yellow = wealth/commerce, green=nature, blue=civilization, white=the sea/deception, black=death and seizing the symbol of each would mark a character with certain related powers, that could be elevated to divine power by using the power of the prison dimension and re-crafting the chromatic realms into their own.

tentacled space monsters, more likely the gods of a prior empire, gone cannibal and insane in their prison dimension) and allow the players to gradually figure out what they might be releasing for the chance at real power and immortality hidden in the prison dimension.

This larger map would allow a single map and related sandbox, with border regions, spreading central corruption, factions and random encounter tables. It might make the module larger, but at this point the module is a quest for immortality, or at least a conclusion where the characters accept their mortality, as Gilgamesh must at the end of his epic. It would also offer the space to really make these universes evocative and strange, even if one kept the overall map fairly small.

Likewise the central fortress of the fallen, trapped gods needs a full redesign. Presumably once opened the gods themselves leave behind the fortress, crafted from the bones of their devoured fellows, because an abandoned fortress city of cannibalized divine skeletons has the mythical stature this adventure needs. The only inhabitants are the corrupted and mad servants and creations of the gods whose corpses make up the fortress, abandoned like rats in the walls when the surviving deities are released. Either a point crawling ruined city (the better choice I think) or an actual dungeon map would work well for this area.

Ultimately, Twilight Calling is a good module, a surprisingly good module, offering a large amount of mystical, mythical weirdness with a minimum of the late 80’s TSR moralism and presenting an esoteric convoluted vision of fantasy divinity that could make for a very fun cap to a campaign. It could use some mechanical fixes, as it suffers a bit from size constraints and a trend towards railroading, but it’s evocative and properly mythical in scale as written, with plenty of ideas worth stealing. The imagery within the module is a bit inconsistent and some of it (green realm, I’m looking at you especially) is trite fantasy cliché, but given that the module is largely about presenting these classic allegorical visions of the universe as playable scenarios and environments it makes a laudable effort at a very hard task.

Saving Throws are an iconic element of table top roleplaying games, that likely has its roots in the First Edition of Dungeons and Dragons, those Little Brown Books (well before that really) . Saving Throws are still a part of Dungeons & Dragons 5th edition, but frankly I think they’ve lost something. Don’t get me wrong, I like 5thedition a lot, and have enjoyed the flexibility of the character generation, the careful balancing of armor class (a real problem area if one is trying to limit power creep) and how despite its heroic elements 5e has maintained much of the feeling of character peril one might get from Basic/Expert style D&D.

Saving Throws are an iconic element of table top roleplaying games, that likely has its roots in the First Edition of Dungeons and Dragons, those Little Brown Books (well before that really) . Saving Throws are still a part of Dungeons & Dragons 5th edition, but frankly I think they’ve lost something. Don’t get me wrong, I like 5thedition a lot, and have enjoyed the flexibility of the character generation, the careful balancing of armor class (a real problem area if one is trying to limit power creep) and how despite its heroic elements 5e has maintained much of the feeling of character peril one might get from Basic/Expert style D&D.

.jpg)